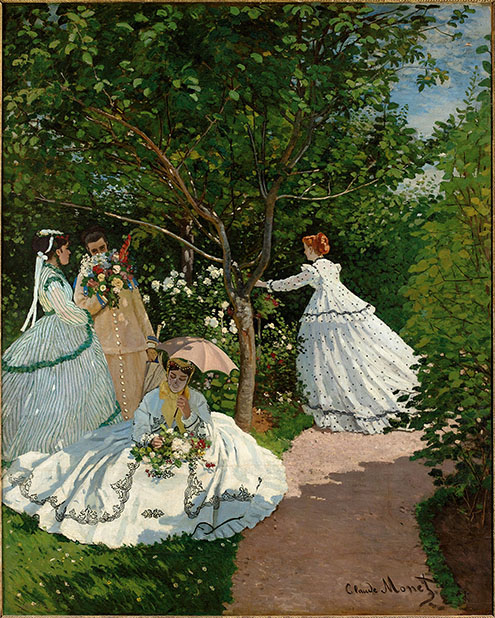

There was nothing but white, yet it was never the same white, but all the different tones of white, competing together, contrasting with and complementing each other, achieving the brilliance of light itself.

— Émile Zola, Au Bonheur des Dames

When my daughter was a young girl she had a favorite white dress, one she wore (almost) to death. Linen and lace and, yes, a blue satin sash at the waist. The kind of garment you give a lot of thought to buying before you actually do, weighing the inevitable smears of chocolate against the pricey preciousness. Suffice it to say we got more than our money’s worth. A girl, if you let her be, has a style very much a reflection of who she is, even at five. (True, the same can be said of boys, especially these days, but there’s more variety to what a girl can wear, which ups the ante a bit.) Some of it remains consistent over the years. Some of it not so much.

Women in the Garden

Style may be more subtext than subject in the tantalizing, soon-to-close exhibit at the Metropolitan Musem of Art, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, but the white dress in more than one gorgeous painting simply pops. Bringing attention to something has a way of reminding you it was always there, but raised now to a level of artistic note, it speaks to the reality that perspective runs much deeper than an artist’s eye. There’s color, too, of course, in all of its Impressionist warmth. And black in its elegance and sensuousness. Like any exhibition, this one comes with a point of view.

At last the subject matter of art includes the simple intimacies of everyday life in its repertoire. —Edmond Duranty, The New Painting, 1876

Down the hall, another gallery, a bit of time traveling connected by the theme of  fashion. Punk: Chaos to Couture in no way measures up to the blockbuster Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (apparently the eighth most popular show in Met history) but it’s a trip so worth taking—a needed jolt in these troubled political times to remind us of the statements made by what we choose to wear. Not to mention the designer forces that gave rise to them. In the words of Vivienne Westwood, who, with her partner Malcolm McLaren, pretty much defined punk style: “The best way to confront British society was to be as obscene as possible.” There’s a lot of black here, and the signature DIY look —ripped jeans, studs and safety pins, bricolage, etc., and with it the suggestion of ways in which high-fashion designers coopted a look borne of working class Britain and middle class U.S.A. Gold safety pins on the shoulder of a sinewy Gianni Versace crepe-de-chine dress may not exactly render it punk, but the point is well taken. And Gareth Pugh’s ball gown made of folded strips of black plastic trash bags layered to look feathery is a statement all its own, echoing, with style and humor, those grand gowns of another time (minus the organ-damaging corsets).

fashion. Punk: Chaos to Couture in no way measures up to the blockbuster Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (apparently the eighth most popular show in Met history) but it’s a trip so worth taking—a needed jolt in these troubled political times to remind us of the statements made by what we choose to wear. Not to mention the designer forces that gave rise to them. In the words of Vivienne Westwood, who, with her partner Malcolm McLaren, pretty much defined punk style: “The best way to confront British society was to be as obscene as possible.” There’s a lot of black here, and the signature DIY look —ripped jeans, studs and safety pins, bricolage, etc., and with it the suggestion of ways in which high-fashion designers coopted a look borne of working class Britain and middle class U.S.A. Gold safety pins on the shoulder of a sinewy Gianni Versace crepe-de-chine dress may not exactly render it punk, but the point is well taken. And Gareth Pugh’s ball gown made of folded strips of black plastic trash bags layered to look feathery is a statement all its own, echoing, with style and humor, those grand gowns of another time (minus the organ-damaging corsets).

Black, the color (or lack thereof) against which others are measured, as in ‘orange is the new black’ (a phrase cleverly taken as the title of Piper Kerman’s reflection on her year in a women’s prison), the irony being that a seasonal color trend is measured against the wardrobe staple for which there is no season. Timeless, basic black.

If it was, indeed, a stroke of good timing that had me seeing these two exhibits on the same day, their lingering effect calls up a truism from the Talmud (alternately attributed to Anaïs Nin): We do not see things as they are, we see things as we are.