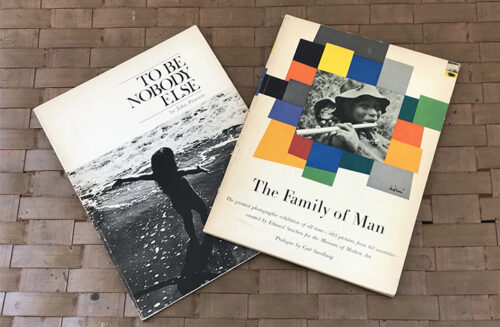

The other day I became obsessed with finding two books I could not easily locate. It was a reference to one of them—The Family of Man—in Sally Mann’s wonderful memoir that set me on my mission. The other book, To Be Nobody Else, bears a connection in my mind to The Family of Man, mostly for the photographs that make for a compelling narrative. They speak to a certain time in my life.

I looked in all the logical places I would have placed them after they’d been released from boxes following completion of a renovation.

I created stories – did I lend them to someone? Did I use them in a writing workshop? Did I share them with a visiting friend who inadvertently tucked them under the sofabed? Books have a way of disappearing, then turning up in unexpected places.

Let it go, I said.

I looked at the same shelves over and over again, a strategy that sometimes works when my mind or eyes are not playing tricks on me.

Are they under a couch?

Let it go, I said. They’ll either turn up. Or they won’t.

But I couldn’t let it go, and my last-ditch effort took me to the last place I would have expected to find them—a crawl space where my husband stores old files. Apparently some overflow boxes from the renovation were tucked away here, until they were forgotten.

I can breathe better now.

* * *

I grapple with letting go. The two concepts—‘grapple’ and ‘letting go’—would seem to be a contradiction, maybe even an oxymoron. Years of doing yoga have me yearning for ‘effortless effort’, that sense of moving from pose to pose with such fluidity that I’m (almost) light as a feather. I have my moments of grace, and I’m thankful for the patience and, yes, the consistent work that has brought me to these moments. But I can’t help thinking the greatest insights come during the plateau phases or the walls we hit when striving for something. It’s the reason I decided to learn to swim at 66.

There’s an image that comes to me sometimes when my breath moves into a slow, easy rhythm during meditation. I’m sitting on the edge of a high cliff, very much at peace. How I got here is beside the point. To watch Alex Honnhold do his free solo climb of El Capitan is to bear witness to being as in the moment as it gets. Letting go is not an option.

Language is my métier. ‘Let go’ is a world apart from ‘let it go.’ One added word brings a pause. The free fall of letting go now has room to negotiate its landing.

***

On a visit that my daughter used as an opportunity to clear out clutter (pre-Marie Kondo) she handed me a small box fashioned from a cut-up manila folder. Decals (a bat and a cat) adorn the outside of this time capsule. Inside is a cornucopia of candy wrappers, her private stash of indulgences not readily available in our home.

I smiled. This was not deprivation by design. Her sweet tooth, like her father’s, found satisfaction enough during family outings, movie nights, birthdays, Halloween. Or so I thought. No surprise that she’s become the baker her mother never was.

As I move into my own decluttering, is it time to let this precious memorabilia go? My daughter insists it is.

***

A very large Webster’s dictionary sits in a cubby all its own in my office. It’s something I acquired many years ago—1962, to be exact—an award with a name as cumbersome as the dictionary itself.

Take a peek. Read the inscription.

Elsa Ebeling—now there’s a name worthy of a short story.

I was just twelve when I graduated from eighth grade. A December baby, I would enter kindergarten before I turned five. In the middle of fourth grade I was plucked out of my class and moved into fifth grade. They called it ‘acceleration.’ I could only see it as displacement, but who was I to complain?

Eighth Grade Graduation Day, 1962. Valedictorian. As if the isolation of being singled out—oh so smart—weren’t enough, here I was standing on a stage looking out at a sea of faces, speaking words (mostly mine) but possibly made a little loftier by a teacher’s coaching. I finished my speech, back to my seat, a sigh of relief. Only to find myself called back to the stage when the award was announced.

I can still feel my heart thumping.

The gift of an oversize dictionary was, is, and will always be cumbersome. It requires a table, maybe even a room, of its own to be of any practical use. We kept it on a low bookshelf. Sometimes I would lug it out for more than a basic definition of a word, other times just to be awed by words and illustrations that might open me to something unknown.

To call it an underutilized, if not underappreciated, tome is an understatement.

Today, as I pull it from its cubby with every intention of letting it go, I can’t help seeing it as the embodiment of a very particular moment in my life much better expressed without words.