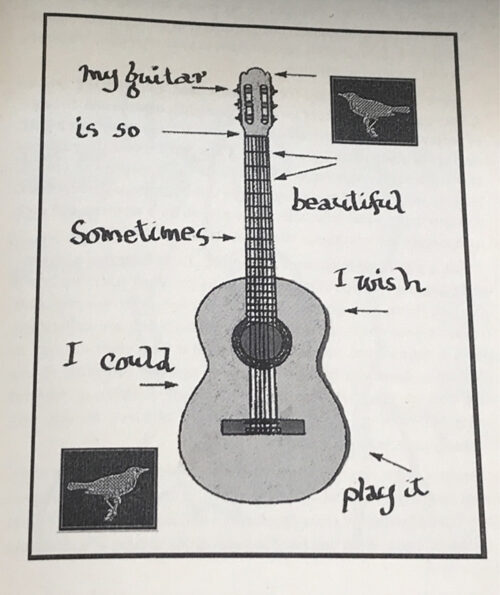

In Leonard Cohen’s Book of Longing, the most recent of his collections, there’s a poem, “My Guitar,” that takes its shape as a drawing, one of many that stand alone or as illustrations paired with poems:

My guitar is so beautiful

Sometimes I wish I could play it

The humility is pure, the phrasing quintessential Leonard Cohen. He is the troubadour of charm, the master of melancholy, the poet that gave rise to at least a fantasy or two of mine when I was young, impressionable, and under the spell of anyone who could show me the way to spin words and/or music into poems and songs. I spent many nights filled with empathy (maybe even envy) for Suzanne, or hoping I just might encounter some of my own sisters of mercy. That’s not to say it was all so personal. He’s a talented (and, yes, handsome) man. I have a great appreciation for what he does, and I had the supreme pleasure of seeing him perform last weekend at Radio City Music Hall.

When I heard him perform fifteen years ago, he was fifty-nine, the age I am now. At seventy-four he is the embodiment of grace. Fans may still cheer when he sings out those ironic, if not self-effacing, lines from Tower of Song:

I was born like this, I had no choice

I was born with the gift of a golden voice

But there’s a different tone to the trope now, an overriding poignancy. To watch Leonard Cohen move with a certain age-appropriate stiffness onstage, to hear his voice, deeper and richer, filled with its own goldenness, is to be in the grip of someone who has faced the darkness and come back a little lighter. Someone for whom ecstasy can be the chords of song, a broken Hallelujah, the touch of a woman, three back-up singers cooing day-do-dum-dum-dum. Someone who captures love and loss and longing with the all-encompassing spirit of a Buddhist and the simple heart of a man.