Tell anyone you’re a writer and inevitably you hear these words—Oh do I have a story to tell! If only I knew how to get it all down. Maybe I could tell it to you and you could write it for me.

“Writing isn’t particularly different from hibernation,” observes the polar bear/narrator in Yoko Tawada’s very inventive Memoirs of a Polar Bear. This is writing at its most artful, even playful, a story offering up both literary and social commentary, something to especially savor during this month in which we celebrate reading women in translation ((#WITMonth). The smaller the world seems, in terms of how we connect, the larger it gets. Diversity, in all its expression of form, feels more urgent than ever.

“Writing isn’t particularly different from hibernation,” observes the polar bear/narrator in Yoko Tawada’s very inventive Memoirs of a Polar Bear. This is writing at its most artful, even playful, a story offering up both literary and social commentary, something to especially savor during this month in which we celebrate reading women in translation ((#WITMonth). The smaller the world seems, in terms of how we connect, the larger it gets. Diversity, in all its expression of form, feels more urgent than ever.

Some say it takes courage to write. For me it’s more surrender, not so much sweet as the kind that comes from all that quiet time spent wrestling with words/thoughts/worlds. Not that courage doesn’t play its part, especially when it comes to telling a story that’s been kept quiet for too long. Unless it’s journal writing, for your eyes only, to write is to imagine you have a story people just might want to read.

First comes a kind of liberation—there! I did it—but once it’s out, the same vulnerability that may have kept you from putting down the story in the first place exposes you now to a world that can be as forgiving as it can be harsh. Did that inner critic we thought so demanding mislead us? Did that muse who lit the fire dissolve in her own ashes?

More than courage, it’s humility that’s on my mind. Madeleine L’Engle expressed it so perfectly in A Circle of Quiet:

“I think that all artists, regardless of degree of talent, are a painful, paradoxical combination of certainty and uncertainty, of arrogance and humility, constantly in need of reassurance, and yet with a stubborn streak of faith in their validity, no matter what.” It’s not about pitting ourselves against the greats, she goes on to say. It’s about a way of looking at the universe.

We are a storytelling species, which means we all have stories to tell. Some are transcendent, some banal. Some are driven by the artful play of words, others by the raw power of the story.

Look anywhere, listen—really listen—to what people say, and a story idea is bound to take shape. The other side of that equation is the story that finds the writer, the one she is simply meant to tell.

Woman at Point Zero. Nawal El Saadawi is a feminist force of nature in her native Egypt and her novel was sparked by an encounter (in her role as psychiatrist) with a female prisoner condemned to be executed for murdering a man. Firdaus, the prisoner, entrusts her story of abuse, female genital circumcision, enslavement, and prostitution to El Saadawi, who shapes it into a compelling narrative that touches on issues that ultimately touch us all. El Saadawi may be the conduit but Firdaus is the hero who turns on its head the question of victimization.

Egypt and her novel was sparked by an encounter (in her role as psychiatrist) with a female prisoner condemned to be executed for murdering a man. Firdaus, the prisoner, entrusts her story of abuse, female genital circumcision, enslavement, and prostitution to El Saadawi, who shapes it into a compelling narrative that touches on issues that ultimately touch us all. El Saadawi may be the conduit but Firdaus is the hero who turns on its head the question of victimization.

Monke y’s Wedding. The time is 1953, the place Southern Rhodesia, the tensions between native populations and the white ruling class growing. Rossandra White spent part of her childhood in Zimbabwe, which makes it impossible not to see her in Elizabeth McKenzie, as spirited a young heroine as it gets. Central to the narrative is Elizabeth’s relationship with Turu, the son of a man who works for her family. And like the best of novels that straddle the YA/adult fiction fence, Monkey’s Wedding lets the wisdom of innocence ring through a complicated political and cultural scenario.

y’s Wedding. The time is 1953, the place Southern Rhodesia, the tensions between native populations and the white ruling class growing. Rossandra White spent part of her childhood in Zimbabwe, which makes it impossible not to see her in Elizabeth McKenzie, as spirited a young heroine as it gets. Central to the narrative is Elizabeth’s relationship with Turu, the son of a man who works for her family. And like the best of novels that straddle the YA/adult fiction fence, Monkey’s Wedding lets the wisdom of innocence ring through a complicated political and cultural scenario.

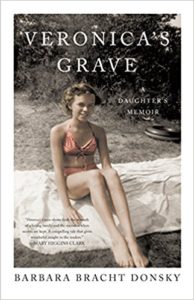

Veronica’s Grave. The opening pages of Barbara Donsky’s very moving memoir take us right into the mind of a young girl who can’t make heads or tails of her mother’s ‘disappearance.’ One day mommy is there, the next day she’s gone, no explanation. People are at her home, crying, still no explanation. And no mommy. A baby brother will surface soon enough, but still no mommy. Like all children, she will find ways to express the confusion, the pain, the anger, and Donsky does an especially skillful job of letting the narrator’s voice change as she herself is transformed.

All of which takes me full circle down a long and winding yellow brick road, with its twists and turns and archetypes and metaphors. Who hasn’t had at least one you’re-not-in-Kansas-anymore moment in his/her life? Who doesn’t need a little more courage, a little more heart, a little more wisdom sometimes, the secret of course being what that trio of beloved characters knows only too well: they’re nothing without each other. I don’t know if there’s no place like home in a world of displacement but I do know there’s no dearth of stories that begin or end there. Some need a little coaxing, others are simply begging to be told.